This post was published first in "Cassandra's Legacy" in 2013. I thought to republish here for the Christmas of 2016. It is not about Christmas, but it describes a story that has a magical atmosphere that reminds the original meaning of Christmas: the birth of the new year. And it remains a milestone for me, one of the stories that, in some ways, drove my life and made me what I am today.

In 1960, Vladimir Dudintsev (1918-1998) published a short novel titled "A New Year's tale." This story greatly impressed me when I read it, many years ago, in an Italian translation in a collection titled "Russian Science Fiction".

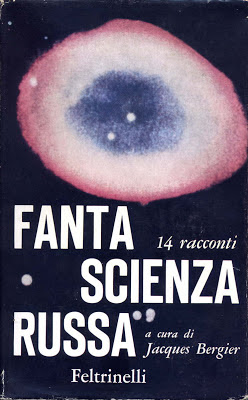

Some 50 years ago, I received as a Christmas present a book titled "Russian Science Fiction." All the stories in that book made a deep impression on me, but there was one that has remained in my mind more than the others; a curious story titled "A New Year's Tale".

I was, maybe, 12 at that time and, of course, I couldn't understand everything of that story and I didn't pay attention to the name of the author. But, as time went by, I didn't forget it; rather, it became entrenched in my mind, progressively acquiring more meaning and more importance. I reread it not long ago, and it came back to my mind during a recent trip to Russia. So, let me tell you this story as I remember it.

"A New Year's Tale" tells of one year of life of the protagonist, a researcher in a scientific laboratory somewhere in the Soviet Union. Dudintsev manages to tell the story without ever giving specific details about anything: no place names, no names of the characters, not even of the protagonist. It is a feat of literary virtuosity; it gives to the story an atmosphere of a fairy tale but, at the same time, it is very, very specific.

It took me time before I could understand the hints that Dudintsev gives all over the text, but after many trips to Russia, everything fell into place. It is curious how Dudintsev managed to catch so well the atmosphere of a research lab in the Soviet Union; he was not a scientific researcher. But that's what makes a great story-teller, after all: understanding what one is describing - and feeling something for it.

The story starts with a debate - rather, a quarrel - that the protagonist has with someone termed "a provincial academic" (we are not told his name). This provincial academic should be nothing more than a nuisance, but the protagonist can't stop from engaging in the debate. He understands that he is losing time, that he should be doing something more useful, more important. But he just can't sit down and do his job.

While the protagonist is entangled in this useless quarrel, the chief of the laboratory (again, we are not told his name), someone who dabbles in archeology, tells to his coworkers of a research of his somewhere in the Caucasus, where they found an ancient tomb. There was an owl engraved on the tombstone and an inscription that could be deciphered. It was, "...and the years of his life were 900...."

Now, what could that mean? Could the man buried there have lived 900 years? No, of course not. But then, what does the inscription mean? Well, someone says, that must mean that this man spent his life so well and so fully that it was like his years had been 900.

The discussion goes on. What does it mean to live such a full life? The researchers try to find an answer but, at some moment, they hear the voice of someone who usually keeps silent at these reunions. We are told that he is from far away, not Russian, that is. We can imagine that this man doesn't have a Russian name, but we are not told names. So, he is an outsider and he comes with a completely different viewpoint; let me call him "the foreign scientist" even though in the old Soviet Union, theoretically, there was no such distinction. "You see, comrades," he says, "it is very simple. To live a full life, you must always choose the greatest satisfactions, the highest joys you can find."

At this point, we hear the voice of the political commissioner of the lab. Apparently, there was usually someone in scientific academies in the Soviet Union who was in charge of making sure that Soviet Scientists would not fall into doing decadent capitalist science. So, he stands up and he tells the foreign scientist, "Well, comrade, don't you think one should also work for the people or something like that?" And the foreign scientist answers, "You are so backward, comrade. Don't you understand? The greatest satisfaction, the highest joy one can have in life is exactly that: working for the people!"

After that the discussion is over, the protagonist of the story reflects on the words of the foreign scientist and he resolves to start doing something serious in his life. He decides to start doing experiments, advance his theory. We are not told exactly what he is doing, but we understand that he is working on something important; a great discovery that has to do with capturing and storing solar light. And he manages to work on that for some time. Then, his colleagues bring to him another paper written by his provincial antagonist. So, he feels he has to answer that, and then the provincial academician replies.... and the protagonist finds himself entangled again into this argument that he can't abandon.

Things are back to the silly normalcy of before, but then something happens. The protagonist finds that he is being stalked. Someone, or something, is following him all the time. When he sees it in full he discovers that it is an owl. A giant owl, almost as big as a man, looking at him. He thinks it is a hallucination, which of course it must be. But he keeps seeing this owl over and over.

So, the protagonist goes to see a doctor and the doctor asks him what made him come there. "An owl," he says, and the doctor pales. After a thorough physical examination, the doctor tells him: "you have one year to live, more or less." We are not told of what specific sickness the protagonist suffers. He asks, "but why the owl?" And the doctor answers, "we are studying that. You are not the only one. The owl is a symptom." Then, the doctor looks at the protagonist straight in his eyes and he says, "I can tell you something. Those who see the owl, have a chance to be saved."

In the meantime, there had been a long discussion between the protagonist and the foreign scientist, the one who had so well silenced the political commissioner. So, the foreign scientist had told to the protagonist his story, obliquely, yes, but clearly understandable. His fellow countrymen had not liked the idea that he had left the country to become a scientist. They are described as gangsters and criminals, but we have a feeling that there was something more at stake than just petty crimes. This man had made a choice and that had meant to make a clean break from his country and his culture; it had meant to accept the new Soviet Communist society. Now, he was spending his time in this new world trying to get his "greatest satisfactions and highest joys" by working for the people. And, because of that, his former countrymen had condemned him to death. So, he had changed his name and his identity, and he had even surgically changed his face to become unrecognizable. But he knew that "they" were looking for him and they would find him at some moment.

So, the destinies of the protagonist and of the foreign scientist are somehow parallel, they both have a limited time. After having seen the doctor, the protagonist understands the situation and he rushes to search for the foreign scientist. They can work together, they can join forces, in this way, maybe they can.... but, in horror, he discovers that the foreign scientist has been killed.

In panic, the protagonist desperately looks for the notes he had collected over the years. But the cleaning lady tells him that she had used them to start the fire in the stove. She had no idea that they could have been important. The protagonist feels like he is walking in a nightmare. Just one year and he has lost his notes. He must restart from scratch.... his great discovery.... how can he do? Yet, he decides to try.

He becomes absorbed in his work. He works harder and harder. Staying in the lab night and day and, when he goes home, he keeps working. His colleagues note the change; they are surprised that he doesn't react anymore to the attacks of the provincial academician, but he doesn't care (which is, by the way, a good lesson on how to handle Internet flames). He still sees the owl; always bigger and coming closer to him, the owl has become something of a familiar creature, almost a friend.

Then, someone appears. It is a woman with well-formed shoulders (of course, we are not told her name). The protagonist recognizes her. It is not the first time he has seen her. He remembers having seen her with the now dead foreign scientist.

The protagonist has no time for a love story. He has to work. He tries to ignore the woman, but he is also attracted to her. He can concede her just a few words. Ten minutes, maybe. So they talk and the woman tells him. "It is you, I recognize you! You can't fool me!" The protagonist remembers something that the foreign scientist had told him; that he had his face surgically changed to escape from his enemies. Now, this woman thinks that the protagonist is really her former lover, who changed again face and appearance and didn't tell that not even to her.

The protagonist tries to deny that he is the former lover of the woman, but, curiously, he doesn't succeed, not even to himself. In a way, he becomes the other, acting like him in his complete immersion in his work. The protagonist discovers that the foreign scientist had assembled a complete laboratory at home, much better than the lab they had at the academy. So he moves there, with the woman with the well-formed shoulders (and the owl comes, too, perching on a branch just outside the window). Then, the protagonist even discovers that the foreign scientist was secretly copying his notes and that he gave them to the woman. She had kept them, the notes are not lost! With these notes, the protagonist can gain months of work. Maybe he can make it in one year, maybe.....

The last part of the story goes on at a feverish pace. The protagonist becomes sicker and sicker; to the point that he has to stay in bed and it is the woman with the well-formed shoulders who takes up the work in the lab. And the owl perches on the bed head. But they manage to get some important results and that's enough to catch the attention of the lab boss. He orders to everyone in the lab to come there and help the protagonist (and the woman with the well-formed shoulders) to move on with the experiments.

In the final scene, the year has ended and we see the protagonist in bed, dying. But his colleagues show him the results of the experiment: something so bright, so beautiful; we are not told exactly what: anyway it is a way to catch sunlight in a compact form: a new form of energy, a new understanding of the working of the sun - we don't know, but it is something fantastic. Even the owl looks at that thing, curious. The protagonist hears the sound of bells from the window. A new year is starting. We are not told whether he lives or not but, in any case, it is a new beginning and, whatever it happens, they'll tell about him that the years of his life had been 900.

And here we are. You see, it is a magic story. It keeps your attention; you want to know if the protagonist lives or not and you want to know if he manages to make his great discovery. But it is also the story of the life and of the mind of scientists that I think you can't find anywhere else in novels or short stories. It is curious that Dudintsev did so well because, as I said, he wasn't a scientist; he was a literate. But he managed to catch so incredibly well the life of a scientist - of a scientist working in the Soviet Union, yes, but not just that. Dudintsev's portrait of science and scientists goes beyond the quirks of the old Soviet world.

Yes, in Soviet science there were things that look strange to us, such as having a political commissioner in the lab to watch what scientists were doing. But that's just a minor feature and, today, we have plenty of different constraints on what we do that don't involve a dumb political commissioner. The point is that scientists often work as if their life were to last just one year; at least during the productive time of their life; when they are trying to compress each year as if it were to be 900 years long. It is their lot: the search for the discovery, being so deeply absorbed in their work, being remote from everyone else; obsessed with owls that they alone can see.

And yet, Dudintsev's story is so universal that it goes beyond the peculiar mind of scientists. It is the story of all men, all over the world, of what we do and how we spend our lives. And the key of the story is the woman with the well-formed shoulders. She recognizes her former lover in the protagonist, or she feigns to recognize him. It is him or it is not him - it doesn't matter, but her devotion to her man is so touching: you perceive true love in this attitude. In the end, that's the key of the whole story: whatever we do in life, we do it for those we love.

Some of us are scientists, some aren't. But it is not a bad advice to live your life as if you wanted each year to be 900 years long. And every new year is a new beginning.