I wrote this document in 1995 in response to a question

from a friend of mine from California. I am republishing it here, in 2015, with some modifications.

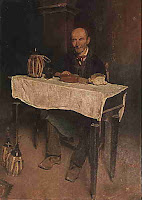

The painting above shows the author's great-great-grandfather, Ferdinando Bardi, around 1890. It was made by his son, Antonio

Bardi. At that time, Florence was already a popular goal of

foreign tourists, but it is unlikely that they would ever have to share - or

even to see - a modest meal such as the one shown here: bread, wine and a bowl of soup. However, it may have been the average

home fare of Florentines of that age.

Food

seems to have taken such an important place in the mind of tourists that

it may have become the main attraction of Italy. It is, however, a recent trend. In the past, there was no doubt in anybody’s mind that art

- and only art - was the reason for visiting Italy. Up to mid 20th century, more or less, visiting Italy in search for good food would have looked both gross and absurd. (*)

Yet, even the old, aesthetically minded tourists had to eat something. So, did they appreciate

the Florentine cuisine of their times? It is a curiosity, but also an element in understanding what was the experience of the many foreign visitors who reported about their cultural experience in Tuscany and in Florence. Can we imagine Stendhal, Hawthorne, Mark Twain, Lawrence, Huxley, and so many others sitting at a

trattoria in Florence? And what would they have been eating, there?

In discussing this question, we face nothing less than an exercise in culinary archeology, and not an easy one, since ancient dishes are not kept in museums and art galleries. At best, we can hope to find written descriptions of what people would eat long

ago, but that's not easy, either.

Until

not long ago,

cuisine was mainly a practical art that people would learn mostly by doing it. Cookbooks did exist, but they were comparatively rare and, typically, directed to the upper class only. In Italy, the quintessential ancient cookbook is "

Science in the Kitchen," by Artusi, published for the first time in 1891. It tells us a lot about the Italian cuisine of a century ago, but nothing about what could have been the actual menu of a restaurant catering to foreign tourists. Besides, the 790 recipes in the Artusi's book are just listed one after the other and the book gives to us little information on which dishes would be standard fare and which ones, instead, would be reserved for special occasions.

But, if we are discussing about what tourists would eat in Florence, then the obvious source should be a guidebook. Unfortunately, even this kind of source turns out to be disappointing for the culinary archaeologist. The oldest guide I could put my hands on is the 1877 edition of the

Guida Manuale di Firenze e de' suoi contorni. It confirms that tourists were supposed to be visiting Florence mainly for its art, as this old book deals almost exclusively with museums, churches,

monuments, and the like. It has only a short section of "useful information"

where we are told of barbers, tailors, hatters, photographers, and all sorts of

services, but nothing about restaurants. It also contains a few pages of advertising:

there are hotels, jewelry, and musical instruments, but, again, restaurants

are never mentioned. The only vague reference about tourists having, after

all, to fill their stomach, is hidden in the advertising from the

Albergo

Porta Rossa (a hotel, incidentally, still existing today). Here, we can read that

tavola rotonda (round table) is available at the

price of 4 Lira. That has surely nothing to do with King Arthur and his knights, but it should be intended as a kind of restaurant where customers would sit together at one or more common tables. Probably, that was the standard kind of food service offered by hotels at that time, but nothing is said in the guide about the menu.

A bit more can be learned from later guidebooks.

One of the most common was the "

Baedeker", often a faithful companion of many foreign tourists in Italy.

I have a 1895 edition of this venerable book, one that might

well have been in the hands of one the characters of Forster's novel "A Room with a View". Its five hundred pages are crammed full of data and maps about art and

museums. It has also plenty of advice for travelers about

hotels, clothes, transportation, and climate. And about food? All we have

is less than two pages. Not much indeed, but something, at least.

First of all, the Baedeker advises the foreign traveler

in Italy to patronize "

first class restaurants," whose menu is

defined as "international". Nothing is said about what kind of menu that

would be, but further on we find a list of "useful words" in Italian that may give us some idea about this point. We have bread, meat, eggs, vegetables,

fruit, and other rather commonplace items. There is no word listed that

could describe a specific way to cook or prepare a certain food. That seems

to mean that there were only a few, standard items in the menu and that preparation was not very varied. Apparently, tourists were not so interested in Italian specialties at that time.

But our Baedeker says more than this, and

it is here that things start becoming interesting. It mentions

"Italian style" restaurants, the term used is "

trattoria," still in use today. We

are told that these restaurants were frequented "mostly by men". Then, one could also

eat at a

caffé, where prices are said to be low and where

the kind of fare described included hot and cold meat dishes. We are also told that these places were always very crowded and that the smoke of

tobacco in winter was so thick that it could become unbearable.

From just

these few lines, we can say that these places were the ancestors of the modern versions of the

caffé and

trattorias still existing in Florence. Surely, we can't find any more the same places described by the Baedeker, but their style may not have changed so much over a little more than a century. With a bit of imagination you can perhaps picture in your mind one

of these crowded places full of those "dark and bloody" Florentines (as

Mark Twain termed them), all smoking and drinking wine. Did ancient foreign tourists patronize these places? Probably yes, otherwise the Baedeker would not mention them. But it is likely that foreigners did that only when they were in dire need of filling an empty stomach.

In later times, the interest about food seems

to have been rising, but only very slowly. In a 1904 travel guide, we finally find an advertisement for a restaurant: the "Restaurant Sport" lists as its main attraction the fact that

English, French, and German are spoken on the premises (no mention is made of the menu). In a 1930 guide ("

Indicatore

Generale di Firenze") we find another advertisement: the

Teresina

restaurant. Here, at last, we are told something about

the style of the food served: it is

cucina casalinga (home style cuisine).

Only after the war we see the interest in food really taking off,

until we arrive to modern

guidebooks, crammed full with advertising for restaurants

almost at every page.

So, old guidebooks just give us some hints of what foreign tourists would eat in Florence in old times, but they tell us nothing about how would they feel about what they were eating. For that, we have to turn to novels and travel diaries. Also here, the task of the culinary archeologist is not easy, but not impossible.

Once we move to old travel diaries, one thing becomes immediately clear: whenever we find

Italian food described, it is always to complain

about how bad it is. So, if we go

back to the prehistory of tourism, when visiting Italy was something

close

to taking a job as a soldier of fortune, we find an early report in the

diary of a French traveler, Charles de Brosses, who visited Italy in

1740.

He doesn’t say much about food, but he mentions that Italian bread is

"

the

most abominable thing one can eat". Much later on, but still in

prehistoric

times in

touristic terms, Stendhal left us a detailed report of his

travels

in Florence and in Italy in his "Rome, Naples et Florence" (1817).

There, he goes on for several hundreds

of pages describing an Italy that looks truly remote to us. But,

about food, he barely manages to mention the existence of

salami, and

to say once that the

gelato (ice cream) was good.

Other old reports

are those of Nathaniel Hawthorne ("The Marble Faun", 1858) and of

Mark Twain ("The innocents abroad, 1867). In both cases we have long and

detailed description of the Italy of that time, but about food Hawthorne

just manages to mention the existence of bakeries, wine and olive oil;

whereas Mark Twain only tells us that he was surprised that he couldn't find any bologna sausage

in Bologna. Not much indeed.

Things changed a little with E. M. Forster's novel "A Room with a View" written

in 1908 and set in Florence around the end of the 19th century. Forster was a meticulous writer who made a point to give all possible details of what he was describing and he may also have had a

genuine interest

in Italian edibles. So, "A Room with a View" starts

with a character complaining about Italian food; an English lady saying:

"

This

meat has surely been used for soup". We can imagine the outraged look of

this middle aged spinster as she works hard at chewing that vile chunk

of meat (we may actually see her in the film that Merchant and Ivory made

from the novel). Surely, also the other British guests of the

pensione

described by Forster must have felt outraged in the same way. Or, maybe, as more experienced travelers,

they had become used to the roughness of the foreign table. Seen with

today’s eyes, this scene is hard to believe. The

English complaining about Italian food? That makes no sense! Things have changed a lot, indeed!

But that is not the only detail about Italian food that Forster provides for us. In the novel, we can also read that:

...... the ladies bought some hot chestnut paste out of a little

shop, because it looked so typical. It tasted partly of the paper in which

it was wrapped, part of hair-oil, partly of the great unknown.

This is not exactly flattering, but it does show some interest in Italian food. (Incidentally, at Forster's

time, "the great unknown" would have recalled the novels by

Sir Walter

Scott). About the oily thing itself, Forster is clearly describing a

castagnaccio,

a kind of pastry that is still made nowadays in Florence and which indeed

does taste somewhat weird.

Castagnaccio is akin to French cheese

with live worms or Japanese slimy

nattoo beans: to like it you must

have acquired the taste for it. It is surprising to read that Forster's characters

bought that rather uninspiring blob of paste because it looked "typical".

That attitude, surely Forster’s own, was exceptional for the time.

Even decades after Forster's the overall attitude of tourists about Italian food seems to have

been rather the opposite: the food eaten by Italians can't be but awful for the palate

of civilized northern people. So, in one of his

ramblings in Tuscany in

the late 20s, D.H. Lawrence was forced to get a meal at a small place in

the countryside, frequented also by mule drivers and shepherds. Here is

how he describes it (from "Etruscan places"):

Everybody is perfectly friendly. But the food is as usual, meat

broth, very weak, with thin macaroni in it: the boiled meat that made the

broth: and tripe: also spinach. The broth tastes of nothing, the meat tastes

almost of less, the spinach, alas! Has been cooked over in the fat skimmed

from the boiled beef. It is a meal - with a piece of so-called sheep’s

cheese that is pure salt and rancidity.

It is a recurring theme: the meat on the plate is the same used

to make the soup. That must have been the nightmare of the British tourists of those times.

Clearly Lawrence wasn’t very happy with his lunch, but at least he gives

us the description of a complete menu. Since he terms it as "usual" we

may imagine that this was the standard fare found anytime one left the

comfortable circle of "international" restaurants. Indeed, what Lawrence

is describing is more or less the standard

family food, as it used to be

in Florence and in all northern Italy up to not long ago: clear soup, cooked

vegetables, boiled meat, and cheese (often the "sheep’s cheese" variety,

that is called

pecorino in Italian). It is not surprising that small

countryside restaurants served more or less the same food eaten at home.

Apparently, the average tourist of old times had to be careful

to avoid being served the local variety of food, or else face the risk

of the wreckage of his or her more sophisticated digestive apparatus.

In a way, this is understandable. During the whole 19th century and well

up into mid 20th most Florentines, just as most Italians, were poor, and

at that time it would have been easy to stumble into bad food, quite possibly

prepared in poor hygienic conditions, to say nothing of the appalling way

of presenting it. But the problem was also another one: at that time, most foreigners seemed to show an evident feeling of superiority

towards Italians, poor and uncivilized in comparison to them. The tourists searched and appreciated only the Italy of the

ancient masterpieces, an Italy of great men and grand enterprises that

probably had never existed, except as a figment of their imagination. This

attitude prevented visitors from appreciating whatever there was of good

- and food in particular - in the real Italy of that time.

It took a lot of time for things to change: for foreign tourists to acquire a taste for Italian food, and for Italians to learn how to prepare it and present it in a better way. Eventually, that led to our times, the "Restaurant Era" of international tourism, Some have said that in our society

food has taken the place of sex as a source of pleasure and, at the same

time, of guilt. Perhaps it is for this reason that our tastes are nowadays

set into all what is exotic, special, native, and untasted before. The result has been, perhaps, the opposite of what was intended. The exasperated search for "native"

food has led to the appearance of food branded as typical and old styled, but that has been developed to satisfy the taste of international tourists. In Florence, I can immediately think of two examples: one is

carpaccio; a completely modern invention, since the idea of eating raw meat would have been simply unthinkable to everyone, Florentines and foreign tourists alike, one century ago. Another is the ubiquitous "Florentine steak." Surely Florentines of old would roast whatever kind of meat they could put their hands on, but this kind of expensive meat would hardly have been a typical food. Even spaghetti and pizza were basically unknown as common kinds of food in the Tuscany one century ago.

All that brings a question: if you arrived all the way to here, it is clear that you are interested in the kind of food that your ancestors would eat while visiting Florence. Probably, you also think that it could not be so bad as Lawrence and others described it. So, if you are really serious about culinary archeology, is there a way that you could reconstruct the

real old Florentine cuisine, as it would be experienced by foreign tourists? Not easy, but maybe, with a combination of luck and creativity, even in a modern restaurant you could find a way to put together something not too far away from the

menu that

Lawrence found so bad.

So, how about thin soup with pasta (

pastina in

brodo)? This is probably the most difficult item to find today in a restaurant,

but, if you are very lucky, you could perhaps still find it in a traditional restaurant under the poetic name of "

stelline" (little stars). Boiled meat, instead, the one used to make soup, is still easy to find under the name of "

bollito misto". It is a true delicacy, served with its accompanying sauces (

salsa verde, battutino, and

rafano). It is also possible to find boiled vegetables (not cooked

in fat nowadays, but usually served with olive oil). And the

pecorino cheese, yes, that's also easy to find, usually as a side dish.

So, you see, it is not impossible. See if you can

accompany this meal with ordinary red wine and you are all set to find yourself in the position of H.D. Lawrence in one of his

ramblings in the savage and exotic Italy of his times and to experience the pleasures of culinary archaeology.

_______________________________________________

(*) My impression is that, in old times, most British visitors would come to Italy mostly to satisfy some unnameable sex urge of theirs, even though they would die rather to admit it. Hence all the rambling about "art," "beauty," and the "Stendhal Syndrome". But don't forget that it was Aldous Huxley who - in 1925 - had defined the Florence as “a third rate provincial Italian town colonized by English sodomites and middle aged Lesbians.” That must mean something.

.jpg)